This is an edited version of a research article I wrote in 2008; one of the most inspiring and fun essays to write for uni, which was reflected in my mark. It’s a left of centre topic, and maybe a bit left of centre for this blog, but it’s just something I’m trying out. Go with it.

When we think of the wonderful world of Disney, trees aren’t usually the first thing that comes to mind—unless you’re a horticulturalist!

You might think of the magic of such classics that bring back childhood memories, like Peter Pan or Dumbo; the crown jewel of Disney that is Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs: or the somewhat negative public perception of Disneyland, Disney World and the subsequent “Disneyfication” of the Western world. The one thing we definitely don’t immediately associate with Disney is trees.

But the tree is a very important aspect of not only Disney films, but the whole universe that Walt Disney created. Did you know that there are over 5,000 different types of trees at Anaheim, California’s Disneyland theme park, including Australia’s own eucalyptus tree?

And in almost every movie the action, at some point, takes place in a forest or woodland area, abundant with lush growth. In Snow White, the title character is stalked by the huntsman and seeks solace in the Seven Dwarves’ cottage in the woods. Sleeping Beauty’s Aurora ponders her future love in the forest amongst her animal friends. Beauty and the Beast’s heroine Belle and her noble steed are attacked by wolves in the snow-covered wilderness surrounding the Beast’s castle.

So where did the mastermind Walt Disney gain his inspiration for the use of trees? Some of his first fairytales he adapted into feature films came from the Brothers Grimm, who wrote Snow White and Cinderella, undoubtedly two of the most popular and well loved fairytales and, thereby, characters.

The Brothers Grimm, writing about the lush green countryside of the European settings for these stories, inspired Disney through their gift of writing. Walt Disney also had a fascination with animals (from crickets in Pinocchio to lobsters in The Little Mermaid ), so much so that he produced a series of documentaries on the animal kingdom and nature, called True Life Adventures. Titles in this series included “Seals Island”, “In Beaver Valley”, and “The Living Desert”. An article on Walt Disney in a 1963 edition of Modern Mechanix magazine said that, “Walt’s early edict for… all the True Life Adventure pictures was to get the complete natural history of the animals with no sign of humans: no fences, car tracks, buildings, or telephone poles.”

Disney wasn’t only interested in portraying animals on film, but also conserving species and their environments for future generations. This is evident in the construction of the Tree of Life at Orlando, Florida’s Disney World Animal Kingdom sub-park. While the tree is fake (it consists of about 100,000 silk leaves sewn onto over 8,000 branches), it has carvings of numerous animals on it, allowing children to experience an African Safari with illustrated depictions of animals that may not be around for much longer.

The “Tree of Life” was drawn directly from the incredibly successful 1994 movie, The Lion King. In the movie, the tree is shown only a few times, where the mandrill Rafiki draws symbols of Simba when his life seems to be in danger.

Gail Krause says that, “… Rafiki is the wise ‘shaman’ of the animal community; he writes the image of the lost and then found king, Simba, on a central tree, making real for himself the ‘death’ and ‘resurrection’ of the true leader—an interesting parallel to the Jesus myth. The Disney company then created the park Animal Kingdom with a majestic Tree of Life…”.

The Tree of Life in The Lion King also serves as a marker for where Simba left his old life as heir to the King of the Jungle and his new life in exile with the feisty meerkat, Timon, and Pumbaa the rotund warthog. The fact that the Tree is in the middle of the desert where scarcely any animal roams signifies the neutrality of the Tree: the halfway point between the corrupt leadership of Scar and the carefree new life that Simba leads.

But the Tree of Life isn’t the only perennial woody plant in The Lion King. The other tree that acts as a signpost for where the action picks up is the almost half-dead, lone branch in the gorge. This tree is the framing point for the stampede that Simba gets caught up in; the stampede in which his father, Mufasa, is killed. It’s not a full, live tree, but its skeleton-like appearance is parallel to the dark, cold soul of Scar and his hyena followers, and the subsequent reign of darkness the animal kingdom is ruled by.

The Tree of Life shows that trees are not only markers for where certain actions will take place or where the central protagonist should turn, but they are somewhat characters in their own right. Trees are key characters/motifs in the Disney films Pocahontas, Peter Pan and Alice in Wonderland, as they provide turning points or revelations in the story.

Mark I. Pinsky, author of The Gospel According to Disney: Faith, Trust and Pixie Dust, says, “Providence will show up in the form of a fairy, wizard [or] talking willow tree,” if ever you should lose your way. Or rather, in Alice’s case, stumbling down the rabbit hole underneath the tree she falls asleep in is how she begins her wayward journey.

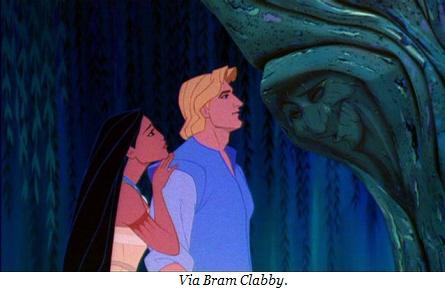

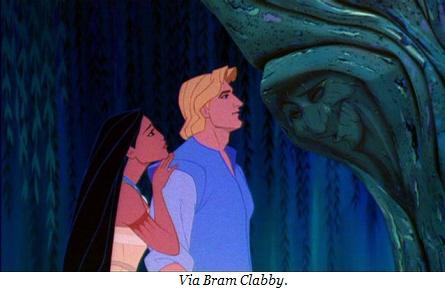

Pocahontas, the story of a Native American girl who promotes acceptance between white settlers and her own people, is the obvious example of a Disney film with a tree as an actual, personified character in Grandmother Willow. According to the Living Arts Originals website, “Willow tree symbolism includes magic, healing, inner vision and dreams… Forests are the abode for the nature spirits”. A lot of research probably went into the character of Grandmother Willow, as these classic Native American qualities of the tree are evident in her. She acts as Pocahontas’s “fairy godmother”. Although Grandmother Willow could be personified as any nationality, she is fittingly a Native American like Pocahontas and her people, because that’s who Pocahontas identifies with (as evident in the conflict between Pocahontas’s tribe and John Smith’s men). When Pocahontas brings John Smith to Grandmother Willow, she shows him her magic and opens up the Native American culture to him, and thereby the settlers, as Pocahontas did in reality many centuries ago. Grandmother Willow, using her virtues of inner vision and dreaming, encourages Pocahontas to follow her path, shown to her by the spinning arrow of John Smith’s compass, thus orchestrating great change in conflict between the “savages” and the whites.

Alice in Wonderland, the most eccentric of all Disney’s films, uses trees in a number of ways. Firstly, the tree in which Alice is studying in at the beginning of the story is the tree under which the white rabbit escapes, and she follows. A magic mushroom (perhaps a reflection of the author Lewis Carroll’s drug use?), makes Alice grow to the height of a tree, where a nosey pigeon refuses to believe she’s “just a little girl!”.

One image of the tree, or woods/forest, that rampant not only in Disney films, but many other contemporary movies, is the personification of the tree—taking on human characteristics, such as eyes and arms, to give off a menacing vibe. In Alice in Wonderland, the Tulgey Woods’ trees observe Alice as eyes appear , which then turn out to be a gathering of characters with eyes—ducks with horns, flamingos with umbrella bodies, and glasses that seem to resemble the fake-nose-and-moustache disguise that children are fond of. Treebeard, in J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, both text and film is another, non-Disney example. The forest in The Wizard of Oz comes to life and the trees throw their apples at Dorothy, Scarecrow and little Toto. If I listed the numerous other movies that show trees in this way, we’d be here all day.

But, they’re all derived from one Disney flick in particular: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. The first ever feature length animated film was also one of the first to depict a forest coming to life in such a way, where the trees grow arms and eyes, and bark floating in the river turns into crocodiles! No doubt other Hollywood productions have used Snow White and Disney as inspiration, especially The Wizard of Oz, with it’s out-of-this-world plot and unmistakably Disney-esque characters.

Even before Snow White, though, was the Disney short animated film Flowers and Trees, shown in 1932, which won the first ever Academy Award for an animated short. This undoubtedly would have been the starting point for trees as more than just “trees”, not only in Disney, but in film in general.

If ever there was a documentary explaining all about the depiction of trees in Disney films, it’s Four Artists Paint One Tree, a special feature that can be accessed via the 2003 special edition DVD release of Sleeping Beauty. In the doco, Walt Disney narrates as four animators go out into the field to demonstrate how they would paint an old oak tree. The first artist, Walt Peregoy, views the tree as an architectural monument, and his finished painting is evidence of the animation of the backdrop of Sleeping Beauty. Josh Meador, an effects artist for Sleeping Beauty, references the Druids, who believed trees had personalities. Maybe he was a key artist in personifying trees and bringing them to life? The next painter, Eyvind Earle, is primarily interested in the trunk, and uses watercolours to fill in the fine detail. Finally, Marc Davis represents the tree as an explosion out of the earth, with branches spraying out from the body of the trunk. After watching this documentary, you can see which aspects of each artists tree, or their style of painting scenery, that has gone into creating Sleeping Beauty. Walt ends the documentary by paraphrasing the artist Robert Henri: “The great painter has something to say. He does not paint men, landscapes or furniture, but an idea.” This seems to be the consensus amongst not just Disney’s approach to filmmaking, but the studio’s approach to letting audiences believe what they want to believe (some would beg to differ on this point).

M. Lynne Bird backs this theory up in her article titled “Ecological Ambivalence in Neverland from The Little White Bird to Hook” in the tome Wild Things: Children’s Culture and Ecocriticism. She discusses the idea that trees are just trees—nature is just nature—in Disney films, but it’s the children’s imaginations, and in turn, Walt Disney’s child-at-heart imagination that makes a tree something more, such as in the films mentioned above. She writes, “‘The Neverland is always more or less an island, with astonishing splashes of colour here and there’… This mix drops nature and privileges both imagination and society. The island can only become real as children look for it.”

Though not a “tree” specifically, the Smoke Tree Ranch, Walt Disney’s holiday home in Palm Springs, California, was used as collateral in the funding of Disneyland. While it was hard for him to part with the ranch, it turns out Disney made the right choice: sacrificing a symbolic and sentimental place in his personal life to create a symbolic and sentimental place for millions of others.

Walt Disney was obviously a kid at heart, as can be seen in the tales he chose to adapt and bring to a worldwide audience. Tarzan’s Treehouse, from the movie Tarzan (and was also adapted from the tree house in Disney’s Swiss Family Robinson) and located in the Disneyland theme park as an attraction, and the creation of the Hangman’s Tree, the home of Peter Pan and the Lost Boys, are more blatant examples of trees in the world of Walt Disney. Hangman’s Tree exemplifies everything a child could want in a tree house.

While, once again, trees are definitely not the first thing Disney-enthusiasts think of when sitting down to watch their favourite film, but the next time you do, keep an eye out for the trees: after all, that’s what a horticulturalist would do!

Elsewhere: [Modern Mechanix] The Magic Worlds of Walt Disney Part 1.

[MSMC] The Cipher: The Mythological Tree in Various Cultures.

[Living Arts Originals] Find Your Tree: The Deep-Rooted Symbolism of Trees.

[Google Books] Ecological Ambivalence in Neverland from The Little White Bird to Hook.

0.000000

0.000000