Even though I live quite close to Chapel Street in Melbourne, I try to avoid going there as it is not my scene at all.

The other night I ventured as far down as I’ve been in years, to Lucky Coq, on High Street, for drinks with a friend.

The outing reminded me of the last time I’d been that far down, which was back in 2008 for a uni project. Odd, I know, but stay with me.

One of my final units was a media subject entitled Men & Masculinities. I was hesitant to take on the course, but it was my final year and I’d already done all the good ones. Aside from my inept teacher, the unit was really fun, and some of the topics I studied have influenced me to this day.

The reason my study group and I trekked to Chapel Street was to examine the different types of masculinities we observed there. With the National Institute of Circus Arts and the multitude of gyms and boutiques located there, I was expecting to see a lot of buff, fashionable men concerned with their appearance. In short, I expected to see the “metrosexual” in his natural habitat.

After a bit of rummaging through my hard drive, and a quick Google search, I managed to find the article—an interview with Professor of English, Sociology & Women’s Studies at the University of California, Toby Miller, by Jenny Burton and Jinna Tay—by which I used to establish some theories about men on Chapel Street.

Keep in mind that these observations were collected two years ago, and I have tried to keep my notes as close to the originals as possible (present day annotations in italics). A lot of the subject matter discussed then has entered our current vernacular; or at least, the vernacular of this here blog, and the ones I frequently read.

Metrosexuality.

“… The phenomenon of the new man, which tends to annex beauty to the wider theoretical works of fashion, with grooming making fleeting, untheorised appearances.”

That’s not so true anymore, as fashion and grooming are becoming as equally important to men who want to look good and take pride in their appearance. Even something as simple as shaving is classed as grooming, and most men we observed on Chapel Street were clean shaven, or at least were doing something different with their facial hair (such as “designer stubble” and goatees instead of a full beard). [Had it been November when the study was done, perhaps I would have seen some mo’s out there?]

“Is the metrosexual a middle- rather than working-class phenomenon?”

I think typically the metrosexual is viewed as upper- to middle-class, and we certainly did see men of these demographics whom you could call metrosexual. However, the working class (tradies, construction workers) could also be seen as metrosexual, because even though they were engaged in manual labour and had “hard” bodies [muscly; evidence of working out], they were still well-groomed and took pride in their appearance.

“Taking pleasure in one’s body, nurturing it, caring for it, protecting it from the elements and so on kind of loosens those old bonds of conventional masculinity, which forbade these behaviours for men and made them taboo.”

The theory here is that men taking pleasure in their bodies and wanting to look physically attractive, for example by going to the gym, is taboo. Do the men we see going to the gym look ashamed of, thereby succumbing to the taboo, or proud of, their hard or soft bodies? (Hard bodies at the gym; soft bodies in certain subcultures like emo, punk, grunge etc.) I wasn’t expecting to see men ashamed of their bodies, especially in a trendy, affluent place like Chapel Street. However, older, out of shape men were a bit more self-conscious than their younger, better-looking counterparts because they tended to look at the ground when they were walking and didn’t make eye contact as much as the more confident men.

“Given all the effort women make to look okay, it seems only fair that men should have to go through something approximating to that level.”

As we expected, there weren’t really any significantly out of shape, badly-groomed or badly-dressed people on Chapel Street. The women took great pride in their appearance, both in their body shapes as well as how they dressed and groomed themselves. This was echoed in the male population, who all were well-dressed, mostly in shape, and well-groomed. In that respect, it could be seen that men are taking a leaf out of the females species’ book.

“… I think it’s [metro sexuality] pretty peculiar to Australia.”

The typical Australian man is seen as a “blokey bloke” in footy shorts and a bluey, doing manual labour and playing sport recreationally. The younger generation of Australian men are challenging this stereotype by being well-dressed, well-groomed and having more unconventional jobs (according to the stereotype) like consulting, fashion, etc. There wasn’t a typical “blokey bloke” that I saw on Chapel Street; even the construction workers, who have the most “Australian” occupation, weren’t physically reflective of the stereotype. In terms of metrosexuality being unique to Australia, it’s true in that a lot of younger men are taking care of themselves, but false in the way that Australia isn’t the only country that has metrosexuals: the US does with Queer Eye for the Straight Guy and the abundance of men in the media who take pride in their appearance and endorse beauty and fashion products, like George Clooney endorsing watches, and Matthew Fox from Lost is the face of a new L’Oreal beauty range for men. I’m not so sure about the UK, because on one hand you’ve got really metrosexual men like Hugh Grant and Jude Law, but on the other there are quite scruffy men like Rhys Ifans, who was engaged to Sienna Miller, and the downright disgusting, like Pete Doherty.

Queer Eye for the Straight Guy.

“… One way to analyse Queer Eye [for the Straight Guy] is as a professionalisation of queerness; a form of management consultancy for conventional masculinity.”

This can be seen in some of the shops on Chapel Street (and Church Street). We saw gyms and health food stores selling protein shakes, etc. in clusters, as well as a beauty salon specifically for men on Church Street.

“… Queer Eye for the Straight Guy is actually about re-asserting, re-solidifying very conventional masculinity.”

Because it separates the “queer” guys, who are fashionable, neat, well groomed, from the “straight” guys, who are messy, unkempt, in need of “styling” by the “queer” guys. Men on Chapel Street challenged this idea. You could speculate about which men were straight and which men were gay, but the stereotypically “straight” ones weren’t messy or “blokey”. There were a lot of business men who needed to look tidy and well-groomed for their jobs, but there were also construction workers whom you would think were typically very masculine and therefore untidy, but even they were taking pride in their appearance, both in terms of their physically hard bodies as well as their grooming.

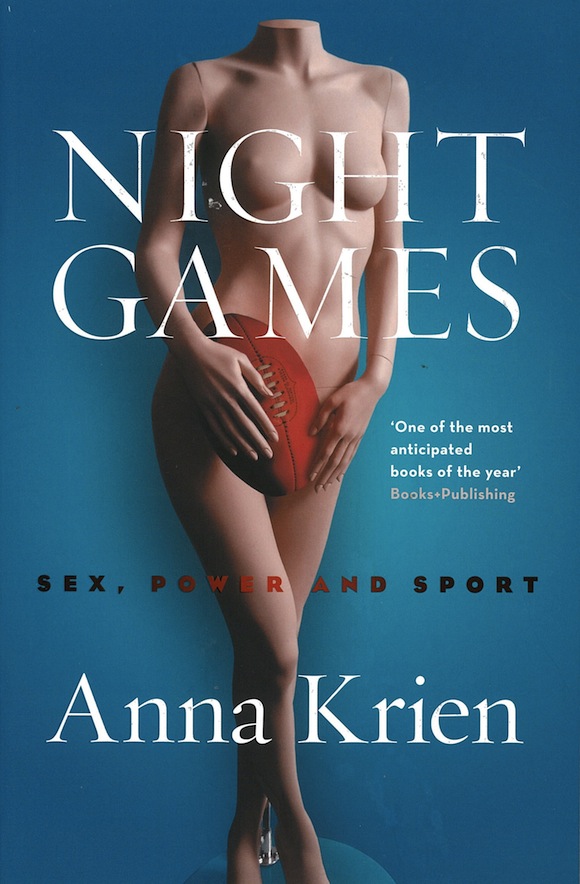

Sport.

“… While it’s still about toughness, sport is equally about beauty, with the NFL now marketing its players as sex symbols.”

While there weren’t really any “sports” men on Chapel Street (apart from the circus/dance performers), the masculinities we observed were as much about being physically attractive to attract a mate as they were about looking tough and hard-bodied.

Eating Disorders.

“… Clearly there are big problems with eating disorders and performance enhancing drugs amongst men… These are partly narcissistic, psychological worries to do with an image to the outside world in general… Male beauty consciousness is primarily a marketing creation… Do men use toiletries and cosmetics because advertising tells them to?”

There were a lot of advertisements on Chapel Street that would support this notion, specifically the ad in the window of a gym/health food store that promotes an unachievable body type for most men. There weren’t as many hard bodies as we expected to see, however the ones that we did see in no way reflected the extreme ideal that that specific advertisement promoted. The men who worked in fashion stores on Chapel Street succumbed to the ideal that that specific store promoted.

“… Eating disorders, insecurity about looks and image, men now being oppressed by the ‘beauty trap’ and so on, but for me this doesn’t allow for the possibility that this may also be a good thing for individual men and conventional masculinity, allowing men to indulge in some self nurture.”

The men on Chapel Street who were well-groomed obviously took pride in their appearance, and weren’t ashamed of the fact that they looked after themselves. The majority of men looked healthy, which therefore supports the claim that male grooming and “metrosexuality” (men taking care of themselves) is a good thing.

Related: The Underlying Message in Glee’s “The Rocky Horror Glee Show” Episode.

Elsewhere: [Media Culture] Metrosexuality: What’s Happening to Masculinity?

[MamaMia] Male Models: Inside Their Straaaange World.